How Deep is the Global Depression?

The world economy is in shock and paralysis

The world economy is being shaken as never before. 2.7 billion workers around the world — 81 percent of the labour force — are under lockdown or travel bans. Hundreds of millions risk acute starvation. And yet, no one knows how deep or long-lasting the depression will be.

The rapid economic collapse and new unpredictable virus make all forecasts preliminary. Great uncertainty will characterize the situation even when it begins to turn. Agencies like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) are forced to put forward three different scenarios, of which their worst is that the pandemic will continue next year.

Already the economy is at a complete standstill in several areas, especially the tourism and hospitality sectors. Investments are close to zero in many industries. Equity markets have plummeted 20 percent or more worldwide. Heavily indebted countries are approaching bankruptcy or ‘sovereign default’.

Global warning signals such as SARS 2002 and the financial crisis of 2008–09 did not lead to any change in government policies. The focus remained on satisfying the parasitic financial and stock markets. Debt levels hit new records worldwide, as did the gap between rich and poor. Welfare and public services were butchered. Jobs became precarious with lower wages. One percent of what the world’s richest man (Amazon owner Jeff Bezos) owns is as much as the yearly healthcare budget in Ethiopia with 100 million inhabitants.

Decades of neoliberal politics have laid the basis for the current depression. In January, the IMF envisaged that the world economy would grow by three percent this year. Now, its forecast is that the economy will shrink by 3.3 percent — or six percent if the shutdown continues in the third quarter (July-September).

Even the more “optimistic” scenario with a decline of 3.3 percent means a fall of 4.5 percent per capita. Compared to 2019, this corresponds to over 800 US dollar less per inhabitant in the world, with the greatest effect among the already extremely poor. The United Nations food assistance arm, the World Food Program, warns that direct starvation could kill 265 million people, a disaster of “biblical proportions” according to its chief.

Additional crisis records are being set in all areas:

• World trade will shrink by between 13 and 32 percent in 2020, according to the World Trade Organization (WTO).

• Commodity prices fell by 37 percent between February 20 and March 20, of which metal and energy prices fell by 55 percent.

• When no oil buyers were available and reserves were full, US oil companies were forced to pay their customers — negative oil prices — for the first time in history.

• In March, finance capital moved 83 billion USD from “emerging economies” in Africa, Asia and Latin America to wealthier countries. So far in this crisis, capital flight is four times greater than during the 2008–09 crisis.

The crisis strikes in all parts of the world:

• In a global survey at the end of February, 75 percent of companies already reported some kind of supply chain disruption — and a majority of them had no ‘plan B’.

• On 7 April, the ILO, another UN agency, warned that 195 million workers risk losing their jobs and more than a billion (1,000,000,000) would become partially unemployed or paid lower wages.

• In Africa, 80 percent of all wage earners are part of the informal economy — wages are paid on a day-to-day basis. With the lockdowns, income disappears completely.

• 22 million have become unemployed in the US within a few weeks, and the forecast is up to 50 million unemployed in May. 35 million of them will also lose their medical insurance.

• Pessimism is also spreading in Europe. The purchasing manager’s index (PMI), used to measure economic trends, has plummeted from 26.4 in March to 13.5 in April in the Eurozone. For economic growth the index should be above 50.

Governments and central banks around the world have launched the largest rescue packages ever. Suddenly, there are hundreds of billions of dollars and euros that go primarily to large corporations and banks. But governments have also been forced to give more money to healthcare and introduce different kinds of compensation for the unemployed. The measures are financed quite simply by printing more money, something that the ruling classes hope to force workers and the poor to pay later.

There are few signs the economy will quickly rebound. We do not know how long the closures will last. The pressure from capitalist businesses to ease the restrictions risks sparking new waves of infection.

Shaken capitalists will start production at a lower level. Upbeat reports say China’s economy is up and running again — but an economy running at 60–90 percent of previous levels means a continuing crisis. Exports and imports from and to China have collapsed sharply, and for many countries China is their largest trading partner.

Capitalist weekly The Economist has a ‘Survival Guide for Business’ that warns of uncertainty, troubled consumers and new health rules. The magazine also predicts a wave of mergers and acquisitions following large scale bankruptcies.

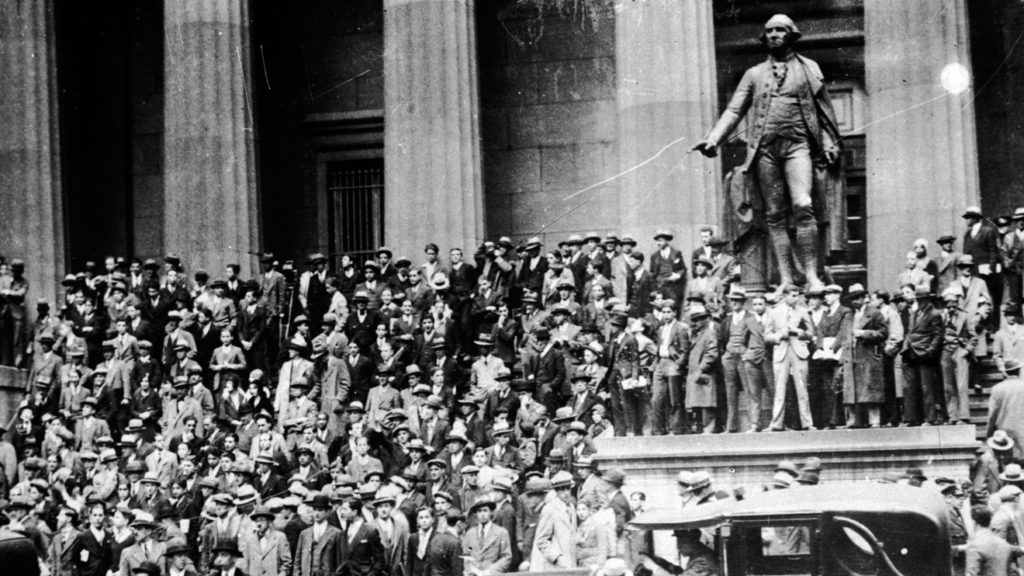

The nationalism and protectionism that increased sharply even before the crisis has now reached new levels that will aggravate the downturn. An important contradiction behind the regular crises of capitalism is that capitalists and large corporations are national, but markets, resources and even production chains are global. During the 1930s, protectionist measures deepened the crisis.

The struggle between US and Chinese imperialism, which also escalated even before the crisis, is an additional major obstacle to recovery.

Washington and Beijing point to each other as responsible for the crisis. The development of parallel systems in technology, finance, power and military alliances is set to deepen. The relocation of production from China was already underway and is now increasing. For example, the Japanese government will now pay companies to move back.

Another factor behind economic crises is what capitalist economists call overproduction and overcapacity. This means that capital cannot sell its products at a profit. It is a fact under capitalism that workers’ wages are less than the value of what they produce. The capitalist buys labour and gets products that are worth more. This, Marx explained, is the production of surplus value and profits, the driving force of capitalism. The worker’s salary is therefore not enough to buy what is produced.

Consumption accounts for more than half of the economy in most countries. In the United States, it accounts for 68 percent of the economy. In China only 39 percent. In recent decades, credit, debt and tax cuts have partly compensated for low wages. The fact that millions are now without jobs or wages, and those who still have jobs no longer can or want to borrow, means consumption can no longer be the engine of the economy. Thus the crisis will be prolonged.

The economic depression highlights the absurdity and cynicism of capitalism: factories that produce weapons and luxury goods are not shut down, while there is a huge shortage of medical equipment worldwide. And the prices of medicine and medical equipment are rising. Capitalism shows its real face, which will have a major impact on mass consciousness and politics.

For socialists such as Socialist Action in Hong Kong and our international organisation ISA, the crisis underlines the great opportunity to change production and the economy in a direction that benefits workers, the poor and the environment.

Instead of restarting polluting factories and production of non-essential goods, democratic decisions and planning are needed. Working hours can be reduced and workers’ knowledge used to transform production.

Socialists, trade unions, climate movements and social movements must mobilize, demand democratic control, in order to abolish the entire capitalist system.